Heo Koo-Yeon in his office

Heo Koo-Yeon is one of the biggest names in Korean baseball history. At this moment, you could say that he is the most influential figure in the Korea Baseball Organization (KBO). Heo was originally an athlete. As a star high school player, he partook in international competitions in the pre-KBO era of Korean baseball. Starting 1982, the inaugural KBO season, he has been a commentator (with a brief detour to a managing job for the Chungbo Pintos in 1986). Outside of the broadcasting job, Heo’s contributed in speaking for the better overall infrastructure and facilities around KBO. He influenced the building of many of the newer KBO venues, which were built closer to the modern style rather than the old high-school style that classic venues adhered to. Most recently, he advised on the construction of the new NC Dinos venue, Changwon NC Park, which is said to be “major league quality” by many. Outside of KBO, he’s also donated close to $100,000 to build Cambodia’s first baseball stadium and helped build a ballpark in Vietman as well. As a baseball lifer who saw the growth of the sport in Korea, he has his vision set on continuing to build baseball in unfamiliar areas.

At 68 years old, Heo is still going strong as a commentator for the MBC while serving as an adviser to the commissioner for the KBO. I sat down in his office to talk about his relationship with MLB, the road to the advent of first Korean major leaguer, and the status of Korean amateur players wanting to sign with a major league club.

Beginning of the MLB – KBO relationship:

As a baseball lifer, Heo, like many others in Korea, was influenced by the Japanese idea of baseball from the time he was an athlete.

“Starting in 1968, as a high school player representing Korea, I’ve been back and forth to Japan a lot,” he recalled. “We knew that our baseball system, at the time, was quite Japan-based. Our leaders and managers were educated during the Japanese occupation era (1910-45).” In 1984, Heo had a chance to go to the United States, thanks to Los Angeles Dodgers owner Peter O’Malley.

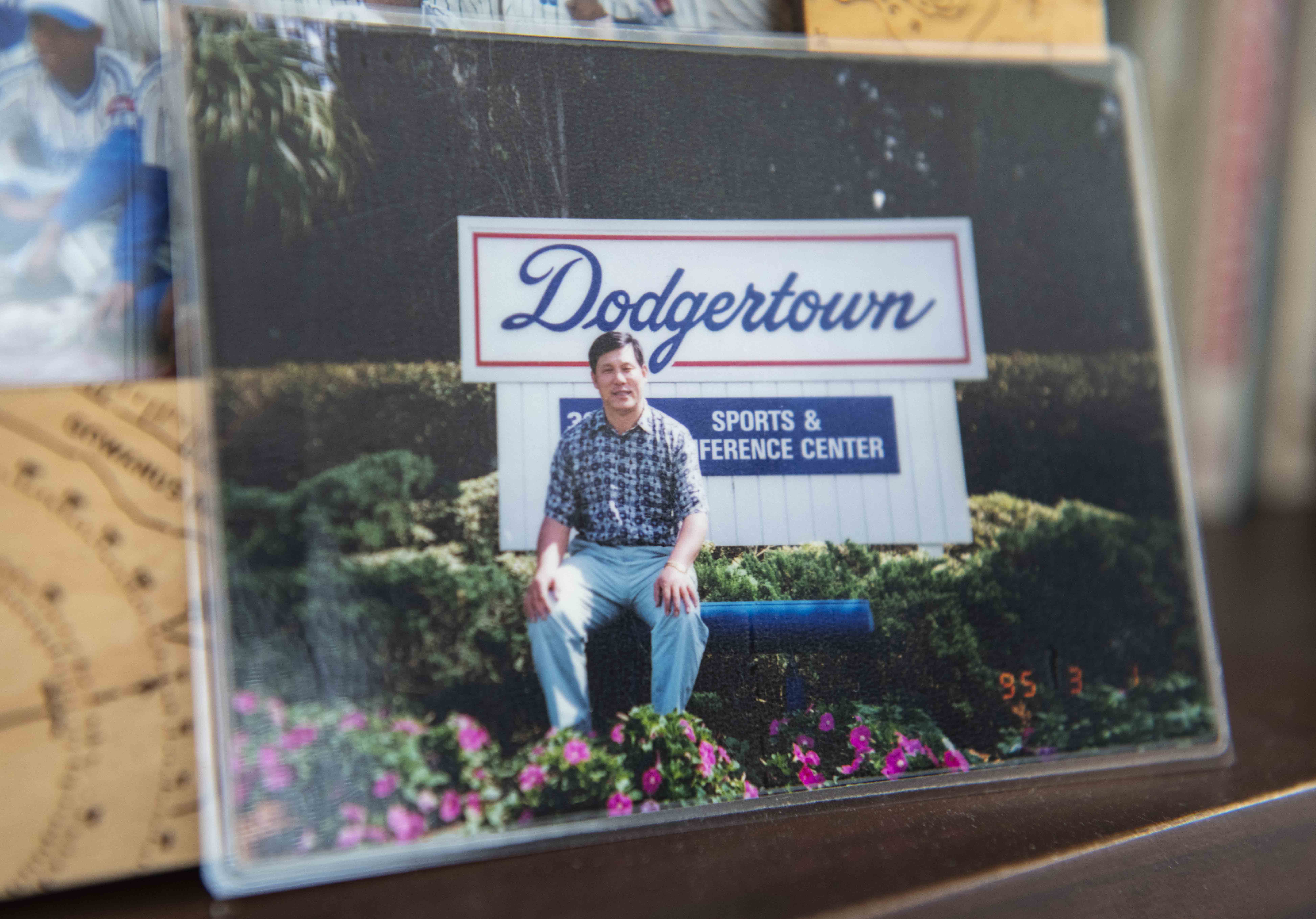

“O’Malley emphasized the globalization of baseball and invited me.” Heo got to go to Vero Beach and Dodgertown for their spring training camp. It was the first time Heo got to see the major league players with his own eyes.

“That, in the big picture, changed and influenced my life,” Heo says. “It also influenced Korean baseball a lot. I would say it was the turning point of our nation’s baseball.”

O’Malley, prior to inviting Heo to the Dodgers camp, had been to Korea before. Through the advent of the KBO, he started to be more interested in it as well. “O’Malley enthusiastically told me to come over and he treated me well,” Heo remembers. At one point, he got to partake in a meal with the O’Malleys, Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda, Dodgers GM Al Campanis, and other front office members. O’Malley introduced Heo to them as “Mr. Heo from Korea” and told them “Let Mr. Heo do whatever he wants at the camp. He has no limitations.” As a result, Heo got to accompany Lasorda and Campanis in Dodgers practices and games.

Heo at Dodgertown

“[Campanis] always had me accompany him at games — even on road games where we had to drive to different venues,” Heo says. In one instance, Heo recalls seeing Fernando Valenzuela icing his arm after an outing. At the time, the common belief in Korea was that pitchers should heat their arm after throwing for recovery. When Heo saw that the very opposite was being practiced in the United States, he asked Dodgers team doctor Frank Jobe. “Admittedly, I didn’t know at the time how famed [Jobe] was,” Heo says. He asked Jobe “Why is [Valenzuela] icing his arm? In Korea, we have pitchers take a hot bath after throwing.” Jobe explained to Heo that that it was “no way to treat an arm” and explained to Heo the science of icing.

“That really surprised me,” Heo says. “So after I came to Korea, I felt the urgency to let others know about it through television. In one of the games I commentated, I said, ‘As I learned in the United States, pitchers should ice their arms after throwing. If they go into hot water, it leads to counterproductive results.'” He also spread the word to managers, coaches, parents, etc., and it led to some controversy. Some reporters would tell Heo that managers would say, “that guy Heo Koo-Yeon became crazy after that trip to the United States.”

Another culture shock that Heo experienced was on infielder techniques. “We used to teach infielders to catch the ball on their chest and with both hands,” Heo says. “They prohibited back-handed catches back then. But in the states, they do it all the time. So I was like, ‘ah, they do it because it’s the quickest way to catch the ball.'” When Heo asked Lasorda about it, the Dodgers manager said “It has been the norm here for like the past 20-to-30 years!” For Heo, it was a massive shock. He realized that, in his words, Korean baseball had been imitating the old-school Japanese style baseball all along.

“I felt it was an urgent matter,” Heo says. “All the technical, theoretical, and systematic aspects of American baseball gave me a wake-up call.”

Later that season, the Samsung Lions, a team that was heavily favored for the Korean Series championship, lost to the underdog Lotte Giants in seven games. “The Samsung group was in shambles after that,” Heo recalls. “I remember that the late Samsung CEO and founder Lee Byeong-Chul was furious about it. At the time, the Lions’ GM was Choongang Ilbo newspaper CEO Lee Jong-Gi, and I kept telling him ‘If you don’t get any external help, you can’t win a championship.'” As a result, Heo recommended the Lions take a trip to the United States for their next spring camp.

Heo told Lee, “[the Lions players] are the most talented ballplayers in Korea, so they don’t have much perspective on how different things are outside of Korea. I’ve seen MLB in action and I learned that our nation’s baseball is not on par with them at all.” Heo suggested the Lions send their players to a major league camp, which resulted in the Samsung Lions heading to Vero Beach in 1985.

Heo also said to Lee, “We are all accustomed to the Japanese style of play, so it’s inevitable that there will be clashes. So just keep an open mind and don’t try to find anything. Listen to their ideas and take it as a learning experience. Take the things you like and ditch the things you don’t.”

When it was all said and done, the Lions completely dominated the 1985 season, going 77-32-1 (a .700 winning percentage) en route to their league championship. Heo deems the Lions’ trip to the United States and their dominance in 1985 as another turning point in Korean baseball history.

“In 1985, we were just learning,” Heo says. “We received a lot of help from MLB that way. There are now more teams that go to the states for spring camp. A lot of baseball people in Korea think this way: if we didn’t get to learn from the majors, we would still be chasing Japan and their ways of baseball. But we were open-minded about American ideas, which resulted in ‘compressed growth,’ meaning that we grew immensely in a short amount of time.” Heo cited Korea’s recent international tournament success in how competitive the nation’s baseball has become — success in the 2006 and 2009 World Baseball Classic tournaments, a 2008 Beijing Olympics gold medal, the 2015 Premiere 12 Championship, and more. For a country whose professional league started only 37 years ago, it’s an impressive feat.

“Nowadays, there’s a lot of ideas exchanged between KBO and MLB clubs, including analytics, player development, and so forth.”

The road to the first Korean major leaguer:

After Heo’s first travels to the U.S., he thought “when are we going to produce a major leaguer?” It was just a dream at the time. The common knowledge is that the first Korean to play in the major leagues was Chan Ho Park. However, there were two right-handed pitchers prior to Park that came close to heading stateside.

The first player Heo mentioned was Choi Dong-Won. Choi had garnered attention from major league scouts thanks to his strong performance at the 1981 Intercontinental Cup. After the tournament, Choi came to an agreement with the Blue Jays and actually signed a contract. “But Choi wasn’t able to go,” Heo recalls. “I know their scout who saw him — Wayne Morgan. He still tells me ‘Choi was one of the best pitchers I’ve ever seen.'” However, things became quite complicated after signing, as Choi hadn’t taken care of his mandatory military service, and at that time, it was not easy to pursue going overseas for Korean men in his position.

The other arm that received major league attention was Sun Dong-Yeol. The Dodgers, with international-minded Peter O’Malley in charge, were interested in him. “In 1982, there was a Baseball World Cup in Korea,” Heo says. “At the time, the Dodgers scout was Ralph Avila, who’s the grandfather of Diamondbacks catcher Alex Avila and father of Tigers general manager Al Avila. When I made it to Vero Beach later, Avila told me that ‘if [Sun] comes over to the majors right now, he can easily win 10 games in a season. I guarantee it.'” Al Campanis, who was next to both of them, asked Heo, “Is there any way we can bring Sun to the Dodgers?”

At the time, Korean ballplayers were quite restricted of their rights to play overseas — or even change teams inside the league. Because the free agency system didn’t exist at the time, players were expected to stay with their original teams for their entire career. Sun was set to join the Haitai Tigers, and it would have brought a huge controversy if he broke off the promise. When Heo told them about it, Campanis followed up by asking “how much would it take? Would $600,000 do it?”

Later, Heo got to catch up with Sun at the 1984 summer Olympics in Los Angeles. Sun did confirm that the Dodgers offered him $600,000 to join them. “He tried to go, but because of the military service issue, he couldn’t. If it weren’t for that, I think he could have gone around 1985 or 1986.”

Choi and Sun ended up having their own legendary careers in Korea. Choi posted a 2.46 ERA/2.30 FIP with 81 complete games in 248 games over an eight-year career, which was cut short due to overuse and arm issues. Unfortunately, Choi passed away in 2011 from colon cancer. As for Sun, in 11 KBO seasons, he compiled a career 1.20 ERA/1.37 FIP, including a legendary 1986 season in which he pitched to a 0.99 ERA in 262.2 IP (while compiling 24 wins, six saves, 19 complete games, and eight shutouts in 39 games). Sun did get to finish his pitching career overseas, playing for the Chunichi Dragons of Japan from 1996 to 1999 as a reliever.

Heo and Chan Ho Park

Years later, when the military rules became a bit more lenient, a pitching star emerged out of Hanyang University in Chan Ho Park, and Peter O’Malley was still interested in bringing Korean talent to his team. Park caught the eyes of major league scouts with his blazing high-90s fastball, and the Dodgers signed him for $1.2 million — a feat that was unimaginable when Heo made his first trip to Vero Beach in 1984.

“From how I see it,” Heo says, “because O’Malley was so interested in Asian baseball, it was just right that the first Korean major leaguer ended up being a Dodger. At Park’s introductory press conference, I remember thinking ‘goodness, 10 years after I was first introduced to the majors, we finally have someone going there.'” To this day, Heo sees Park as a Neil Armstrong-like figure, taking the first step as a Korean in the majors.

Korean Amateurs and MLB:

Since Park’s success in the majors, more scouts turned their attention to finding talents in Korea. Teams signed and developed talents like Jae Weong Seo, Byung-Hyun Kim, Sun-Woo Kim, and Hee Seop Choi. This of course came with a bit of a pushback. Heo recalls that major league officials told him that Korean baseball people started to react quite sensitively towards teams trying to sign the nation’s top talents.

“One caveat about Korean ballplayers is that they have to take care of their mandatory military service,” Heo points out. “That’s a huge dilemma. What are you going to do about it? You have to rest for two years. Back in the day, it was closer to three years. That’s a huge pause for your career.” Players like Chan Ho Park, Shin-Soo Choo, and Byung-Hyun Kim were granted military exemption for international tournament accomplishments, but it’s far from being a sure thing for any players to receive that benefit.

Heo also adds that growth takes more time for positional players, and major league teams may have figured out that the success rate has gotten pretty low with Korean amateurs.

“There are a lot of things to adjust to,” Heo says. “Customs, language, new atmosphere, etc. It’s hard to fight through those differences. It took time for teams to understand that and the amount of IFA signings out of Korea have reduced.” At this moment, the only active Korean major leaguers that went through the minor leagues are Shin-Soo Choo and Ji-Man Choi — a small number considering how many Korean talents major league teams have signed over the years.

There are many factors that go into impeding Korean signees’ success in professional baseball in the United States. “When you put 18-to-19-year-old Korean kids in a U.S. minor league system, it’s hard for them to acclimate to such an atmosphere.”

Heo notes that, in Korea, amateur players are trained in groups and are led pretty much exclusively by their coaches. In the U.S., while players do receive instructions, they grow their game in a more independent fashion. “[Korean high schoolers] are accustomed to doing what they are told,” Heo says. “More than 90% — I might even say 99% — of amateur baseball here is quite group-oriented, and they are taken care of by the school and parents. And all of the sudden, they are left off in an unfamiliar atmosphere where they have to figure everything out by themselves. In the U.S., a lot of kids were educated to be more independent and self-sufficient. Also, there’s the difference in leadership. In Korea, the coaches and managers have a say in everything that players should do. It’s almost like a one-on-one coaching with every player. So when they get to minor league ball, it’s hard for them to think on their own and improve their skills.”

Heo adds that the road is even tougher for infielders. “There’s not been a Korean infielder, who signed as an IFA, that became successful in the U.S.,” mentioning former Cubs and Rays prospect Hak-Ju Lee as an example. “In the past, there were guys like Kaz Matsui and Tadahito Iguchi out of Japan, but I think major league teams have become more aware of the lower success rate of Asian infielders. It’s really hard to possess major-league-level flexibility, agility, and arm strength all at the same time.”

Heo looks at players like Hyun-Jin Ryu, who was drafted by the Hanwha Eagles of the KBO, spent the first seven years of his career in Korea, and was posted to the major leagues before the 2013 season. “Nowadays, because the KBO has a posting system and free agency, it’s better to establish yourself as a more sure major league prospect after getting playing experience in the KBO. Stay in Korea, play in the KBO, iron out their skills there, and go to the U.S. via posting or free agency.”

“In my point of view,” Heo says, “that the success rate of Korean high schoolers in the U.S. is less than 5%. But I do understand that players have dreams to make it big. It’s like the band BTS getting to play a big show in places like Wembley.”

출처 - https://blogs.fangraphs.com/how-one-man-changed-korean-baseball/

저작권 문제 시 연락주시면 삭제하겠습니다.